Planetary Annihilation and the Art of Robotic War

It only takes a glimpse of Planetary Annihilation to understand that it thinks big. This real-time strategy game doesn't have you waging war on a county, or a country, a continent, or even a single planet. Instead, you set your strategic sights on a number of planets at once. You don't manage only a battle or two at a time; instead, you command your robotic forces across all these planets at once, collecting resources and fending off the enemy's metal warriors as they vie for dominance. In an individual match, a solar system is at stake--and in this early-access game's newly introduced Galactic War mode, an entire galaxy hangs in the balance.

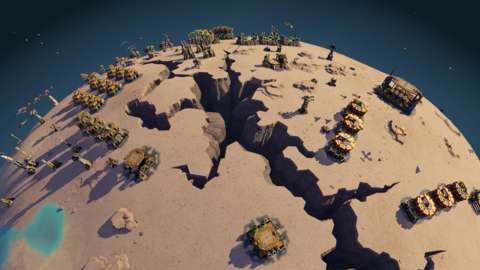

Planetary Annihilation's presentation is its most immediately striking feature, if only because the planets that represent individual warzones look so stunning against the darkness of space. And you spend a lot of time playing Planetary Annihilation with an entire planet stretched across the screen--a planet around which you can rotate and zoom the camera to your heart's content. Mind you, these planets aren't the size of the Earth, or even our own moon, unless you imagine that even the game's smallest units are the size of entire cities, and production facilities are as expansive as Australia. But whether you think of the planets as rather small or the robots as rather large, Planetary Annihilation is awesome, and awesomely overwhelming, at first glance.

If you've played Total Annihilation or Supreme Commander, however, you are already prepared for Planetary Annihilation's impressive scale. You've already commanded forces from a distance so vast that your robots are represented by mere icons. You've already nuked an enemy commander, a super-unit that serves as your moral and mechanical center. Planetary Annihilation is the next logical step in this sequence, and the game's economic structure, robot designs, and general themes echo the great Chris Taylor-designed games that preceded it.

If this all sounds like a bit too much for you to handle, fear not: developer Uber Entertainment wants you to focus on the strategizing, not on the micromanagement. I checked in with Jon Mavor, the bright mind behind Planetary Annihilation (and lead programmer of Supreme Commander), to see just how the development team keeps battles manageable from one moment to the next. The key to maintaining order is a suite of mechanics called advanced command and control. Says Mavor, "With area commands, for instance, you can automate production by queuing up multiple factories and resource structures with simple drags and clicks. Picture-in-picture, another tool, lets you interact with multiple planets across two windows. Our notification system dynamically lets you keep track of battles. And with automatic rally point, patrol paths and build orders that repeat, we take away the need to micromanage all of your factories. For example, you can have a rally point that leads from a factory to a teleporter that then rallies the unit to attack an enemy base on another planet."

I saw several of these mechanics in action, only to wonder why I'd never seen them in a strategy game before. I've seen automated rally points certainly, but being able to queue up a number of power structures without having to manually choose their location is a godsend. (Shift-clicking into place ten power stations seems such a quaint but tedious option, in comparison.) Picture-in-picture, too, is not only vital to managing two planets at once, but is visually astounding to boot. That second planet is not represented by a minimap; it's a full-fledged rendering of another world in the corner of your screen, and can be fully manipulated in its window. More astounding is how well the game performs. Zooming in close reveals plain-looking units and geometric trees, but you spend most of Planetary Annihilation from much further out, and from those impressive distances, the game looks far more artistically vibrant than Supreme Commander ever did. In Mavor's words, they are "light, clean, and colorful," and they look all the more splendid given the game's smooth, brisk frame rate.

Mavor adds, "Making a game look good starts with art direction and ends with the technology to pull it off. Over the course of the project we've revamped and extended each of the systems to improve visual quality. Typically we look at the game in terms of close zoom, medium zoom, and far zoom. In each of these areas we try to optimize the visual look as much as we can. Doing natural lighting lighting and shadows on moving planets in a real solar system that has to work from any point in the system is actually pretty challenging. A lot of the little visual tricks we use in a normal level don't actually work, so we've had to invent quite a bit of tech to make it work. Obviously, there can be a collision between gameplay and visuals. For example we do have icons and other [interface] elements that can get in the way of the just looking at the planets."

Mavor is also quick to point out Planetary Annihilation's greatest visual trick. "Ultimately, what's most important is that when we smash planets together it looks awesome," he says, and I could see why it took such priority while watching a dwarf planet collide with a primary planet. It takes a while to research the technology that allows you to create such an event, but what an event it is. The soundtrack bursts with anxious violins, a virtual choir belts out its discontent, and hundreds of pieces of the planet's crust burst into the air, laying a once-vibrant landmass in ruin. In the example I watched, that crater then filled with water, making the destruction look all the more dramatic.

A planetary collision is a disaster, but not necessarily the end, presuming your remaining commander was not destroyed in the blast. However, rebuilding becomes a priority, and the newly terraformed planet may force you to rethink your tactics. Luckily, the streaming economy, which doesn't require you to pay for structures up front, helps kickstart that process. Says Mavor, "This lets you queue up dozens and dozens of structures and create deeply strategic, forward-thinking plans on the fly. You boost your build times by acquiring more resources, so as you can imagine, you see lots of fighting around resource hot zones. Players constantly expand so they can fuel their production and eventually travel to other planets to eat up more."

Lest you forget, the smoking remains of the impacted planet are not your only source of raw materials. "Another strategic consideration that's different from other games is that your economy spans multiple planets," says Mavor. "When you own your own planet in Planetary Annihilation, you have an incredible resource that allows you to build massive armies. The strategic implications of exploring the planetary system during a long game is staggering. When players start on different planets it changes the character of the match entirely."

Mavor tells me that Planetary Annihilation is not just a game for nostalgic Total Annihilation fans, but for everyone. The new Galactic War mode in particular sounds like a great place to start, as it is focused not on multiplayer battles or skirmishes versus the AI, but on a procedurally-generated single-player journey that has you earning technology randomly, and more slowly, than in a single match. Those technological limitations sound like a great way to ease in newcomers, so if you were previously too intimidated to take to the stars, now might be the time to plan your voyage.

Uber has yet to finalize a release date, though as is the case with any early access game (or indeed, most modern games), Planetary Annihilation's development will not end when the game is fully released. The team still has a lot in store, though I suspect that this feature-rich RTS game will soon grow out of its current gamma phase, at which point you should look for me on the battlefields. I'll be the one flinging a frightening sphere of doom into your planet's orbit.