Elite: Remembering the Original Open-World

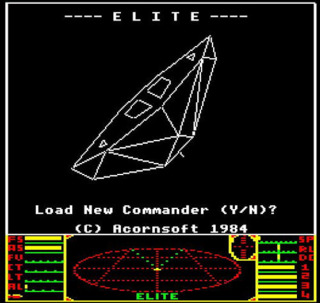

I was maybe a little young to have fully appreciated the space trading classic Elite the first time around. It was released nearly 30 years ago on September 20, 1984--a whole year before I was even born--and it wouldn't be until the age of 10 that I got a glimpse of its rudimentary wireframe models running on an ancient BBC Micro at the back of my primary school classroom. And while games had come a long way by that point, with the Super Nintendo and Sega Mega Drive (Genesis to those in the US) both on the market, there was something fascinating about loading Elite with text commands from the Micro's comically large 5 1/2-inch floppy disks.

Not that I could ever play it properly. Elite was hideously complicated; flipping through the game's famously large manual (thankfully preserved online), gives you an idea of just how elaborate and impressively detailed the mechanics were; the docking procedure alone was enough to give even the most experienced Elite players sleepless nights. While most games at the time stuck to the simple cash-extracting ideas of the arcade, Elite took a different approach. There were no missions to guide to you through the game, nor was there a leaderboard of high scores to track progress. Instead, you were dropped into a vast procedurally generated universe with a singular goal: become an Elite space pirate. How you got there--within the game's few constraints, of course--was entirely up to you.

"I was always convinced you could do 3D on a computer," Elite co-creator David Braben tells me," and I got an Acorn Atom and spent time and actually got a game up and running where I had four different spacecraft--all of which made it into Elite--and you could fly them around, and it was called Fighter. But it had the same problems as the other games. Once you have a certain opponent and you beat them, the next opponent has to be harder. You end up with a very tight game loop that just doesn't go anywhere. It has to become preposterously difficult to have enough longevity."

What Braben and co-creator Ian Bell came up with instead was one of the first truly open-world games. You could spend all your time in Elite trading, diving into the game's deep economic and political system that influenced the price of goods based on the demands of planets and the cash you had to hand. Too civil for you? You could try illegal trading, dealing delightful items such as firearms and narcotics to planetary systems while trying to avoid recriminatory action. Or, if combat was more your thing, you could become a bounty hunter and destroy pirates, or become a pirate yourself and hijack the cargo of passing freighter convoys. Pacifists could mine asteroids for ore, and scoop up the dropped cargo of destroyed trade ships.

Elite was a revelation. No two players had the same experience playing the game. Its groundbreaking open world, its cutting-edge wireframe 3D visuals, and the believability of its universe made it one of the most influential games of its generation, and not just in the subsequent explosion of space simulators like Tie Fighter, Wing Commander, and Descent: Freespace that flooded the market after its release. Elite was also a technical marvel, a lesson in efficient programming and game design for the rapidly growing development scene in the UK. "Elite was a particular achievement, because of how they compressed such a huge game into such a small space," X-COM creator Julian Gollop tells me. "They had to compress the game into 16K using the [BBC Micro's] high-res mode, so it was a pretty amazing feat. It was the kind of programming that just isn't done these days at all, and probably hasn't even been done that well since Elite was made."

Storing an entire galaxy within the confines of the BBC Micro's 16kB of memory was indeed no small feat. To do so, Braben and Bell came up with an ingenious method of procedurally generating everything using a clever algorithm that stored hundreds of different planetary names and configurations as a mathematical formula, rather than as raw data. "When putting together the world, I remember thinking, 'How many locations can we have?' says Braben. "And I thought, 'If we have 20, that's 20 bytes per location, and what can we do with that? That's barely a name.' And that was still quite a lot of memory in those days. And then I thought, 'Ooh, I know! What if we used the name, and the first letter could be the type of system, and we could generate the whole lot?' That was the eureka moment."

But even with the pair's memory-saving algorithm at work, every byte used was under scrutiny. "We spent a lot of time doing something that we called byte savings, where we pored over the code and found a way to save three bytes, and then maybe another four. We knew what we were going to spend them on. So, with Galactic Hyperspace, I remember we needed to save something like a total of 16 bytes. That included the text string and the code and everything, which today sounds ridiculous. We worked exactly how we'd do it, and how we'd change it with one byte here and two bytes there, and eventually we had it."

After Elite's 1984 release on the BBC Micro, it was ported to nearly every popular '80s game platform around, including the ZX Spectrum, Apple II, and Nintendo Entertainment System. Braben would go on to form Frontier Developments, a studio that has created games such as Elite's sequel, Frontier: Elite II, as well as more modern games like Kinectimals and LostWinds. But it's Elite that stands out as Braben's greatest gaming achievement.

"The main impact Elite had wasn't in space games" says Braben, "but in games generally Prior to Elite, publishers were very narrow about what games they would sell, because they knew what sold, which is a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. It was after [the release of Elite that] we saw a lot of games that were very, very different, that didn't fit into the mould, that were new genres. That was Elite's real legacy; it freed games. Within five years, games got back into a rut, but at least it was a deeper rut; there was more variation. Elite changed things around, and showed that you can be very successful outside of that."