Half-Life 2: The Anatomy of a Classic – Part One

"Wake up and smell the ashes."

These words from G-Man, spoken just moments after Half-Life 2 begins, resonate throughout the game. There are plentiful theories as to who this man is, who employs him, and what his relationship is to Gordon. But Half-Life 2 is not one of the greatest games of all time simply because the G-Man speaks such mysteries with his halting voice, but because it is so thoughtfully assembled and thematically consistent.

Of course, a few thousand words isn't enough to express what makes Valve's masterpiece so enthralling. I have much to share with you--so much, in fact, that I want to close out Video Game History Month with a multipart analysis. My dissection isn't intended to speculate on the story elements that give rise to so many wonderful theories and extrapolations. Instead, I hope to look at its various mechanics, narrative devices, and map designs--to explore the anatomy of Half-Life 2. And its birth begins with a gaunt G-Man's call to action, and a train ride to City 17's rail station.

One Man, One State

Once the opening credits conclude and you disembark, you immediately understand that you are not an aggressor--and that the Combine soldiers are in control. Should you draw too close to a soldier, he will shove you backwards, and it's hard to forget the soldier who later asks you to pick up a soda can and drop it into the nearby wastebasket. This is a small touch, no doubt, but it's a great example of how gameplay and story can be merged in a single interaction. Mechanically speaking, the game is teaching you how to pick up and drop objects, if you haven't already figured it out. Narratively speaking, the game is reinforcing who is truly dominant--and it isn't you. This is a theme that Half-Life 2 returns to time and time again, and one that allows it to stand proud among shooters a decade later. Where the majority of modern shooters make you the aggressor, Half-Life 2 is no power trip. In fact, you spend a good while without a weapon in your hands. That may sound boring, but Half-Life 2 keeps your attention by giving you a number of sights, sounds, and events to ponder and analyze.

Consider, for instance, the vortigaunt you glimpse within a station. He is sweeping the floor and closely watched by a nearby Combine grunt. The alien may look odd, but he is performing a mundane duty. Note the collar and other hardware attached to his body. You immediately understand that the vortigaunt is either subservient or enslaved, and in one small stroke, Half-Life 2 casts these aliens not as threats, but as allies, or at very least, victims of the Combine. All of this exposition occurs at your own pace. Half-Life 2 does not introduce you to these concepts by having one of the nearby residents catch you up on current events or explaining the circumstance in an opening narration.

Instead, Half-Life 2 remains a masterclass in environmental storytelling. Dr. Wallace Breen's "welcoming" telecast is particularly noteworthy not just in how insincere his words sound, but in the kind of language he uses. The word "benefactor"--the word he uses to describe the faceless ones who have seemingly imprisoned humanity--is a not-so-subtle attempt to characterize these beings as benevolent (clearly, they are not), but also harks back to Yevgeny Zamyatin's novel We, which is largely considered to have inspired Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, to which Half-Life 2 is occasionally compared. We is one of the first depictions of a dystopian future that satirized the author's culture--in this case, Soviet Russia. Its world is presided over by a man known only as The Benefactor, and its citizens are known only by numbers.

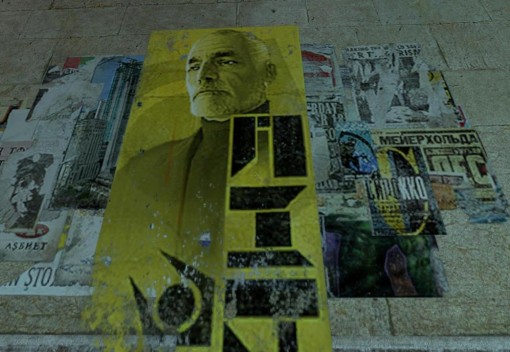

City 17 and We's One State are different, of course, and the plots of these works aren't particularly parallel, but the similarities are worth noting, particularly in light of the Combine propaganda on the walls. Consider the poster featuring Breen looking off into the horizon in a pose long associated with an individual facing a brighter future. Soviet propaganda often depicted Stalin and Lenin in similar poses, as you can see below, and given the Cyrillic text on these posters, the references to Soviet Russia seem obvious. Half-Life 2 doesn't take place in Russia, most likely, though City 17 is assumed to be somewhere in Eastern Europe. I'll let devoted Half-Life 2 theorists debate about City 17's exact location; I am more concerned with how these small details communicate totalitarian ideals without the game expressly spelling out the backstory. If you're an American, particular one that lived during the height of the Cold War, the Cyrillic text communicates the kind of otherness you were taught to fear. We'll visit this subject later as we rush through the canals and make our way to Nova Prospekt.

Of course, systemic oppression wasn't the exclusive domain of Soviet Russia. Consider Breen's own words: "And so, whether you are here to stay, or passing through on your way to parts unknown, welcome to City 17. It's safer here." Safety versus freedom is a frequent theme in an age where we are taught to fear terror by a government that would violate our privacy in the name of security. With the jingoism of Call of Duty and Battlefield finding more prominent roles in modern games, Half-Life 2 provides a vital counterpoint.

Basic Instinct

Just after Barney arrives, dressed as a Combine soldier, Valve raises the fear factor, showing you glimpses of presumably violent interrogations occurring behind closed doors. If you're worried, you needn't be, of course: Barney uncovers his friendly face just moments later, and you soon emerge into City 17. It's a fantastic reveal for its immediate impression of openness, followed by the realization that the Combine are watching, documenting, and imprisoning as much as possible. That freedom-versus-confinement dichotomy plays out in a number of ways. You see buildings in the distance and the Citadel rising above you, but the Combine's blockades confine you. A hotel and souvenir shop greet you, but they are boarded up and abandoned. It's the nature of most shooters--and games in general, for that matter--to provide a sense of a greater world while limiting your freedom, but Valve finds a way to make this gaming convention make sense in its world. The Combine have a vested interested in limiting your movement. There is no control when you cannot leash your subjects.

Before you emerge into City 17, however, listen to Breen's second telecast in which he responds to a supposed letter written to him about overcoming instinct, the instinct in this case to reproduce. No surprise: he is once again echoing major themes of the Soviet era, in this case espousing the concept of the "New Soviet Man." Here are some of Breen's words: "Instinct creates its own oppressors, and bids us rise up against them. Instinct tells us that the unknown is a threat, rather than an opportunity. Instinct slyly and covertly compels us away from change and progress. Instinct, therefore, must be expunged." Compare them to Leon Trotsky's words in Literature and Revolution: "Man will make it his purpose to master his own feelings, to raise his instincts to the heights of consciousness, to make them transparent, to extend the wires of his will into hidden recesses, and thereby to raise himself to a new plane, to create a higher social biologic type, or, if you please, a superman." The New Soviet Man's goal was to triumph over his own instincts.

Superstition, which lies at the root of ritual, must, of course, be opposed by rationalistic criticism.

Leon Trotsky, The Family and Ceremony

Let me remind all citizens of the dangers of magical thinking. We have scarcely begun to climb from the dark pit of our species' evolution. Let us not slide backward into oblivion, just as we have finally begun to see the light.

Dr. Wallace Breen, Half-Life 2

Gordon still has no offensive capabilities, but he is absolutely capable of taking damage. The apartment escape sequence initiates Half-Life 2's primary narrative arc, which begins with a vulnerable Gordon on the run, powerless to fight back, and ends with him at the forefront of a revolution. These moments leading to your first encounter with Alyx Vance are self-explanatory, but they provide an effective glimpse at the lives of City 17's citizens, who live sparsely, and in constant fear. Alyx's introduction, however, is notable for how it subverts the common damsel-in-distress trope, with Alyx in the role of savior, and Gordon in the role of victim. Of course, Gordon is this world's true chosen one (more on this later), but Alyx is a leader in her own right, and it's a shame that she doesn't earn more screen time.

Now that Alyx has brought you to relative safety and you've been reunited with Barney, you collide with the telling traits of lean storytelling: there are few activities or lines of dialogue that don't have purpose. The upshot to lean storytelling is that you spend less time listening to other characters telling you about the world and more time seeing it for yourself. The downside is that you can infer future events from minor details. Every line of dialogue or story event either moves the plot, develops a character, tells a joke, or foreshadows the future. "I still have nightmares about that cat," says Barney, and Alyx replies with slight panic, "What cat?" We now know not only that the teleporter is unsafe, but we can presume that Gordon's transfer to Eli's facility will not go according to plan. The shenanigans of Lamarr, the de-fanged headcrab, occur just afterwards. Hmm--could it be that Lamarr is going to disrupt the transfer?

Well of course that's what it means, but at least you get to play around a little beforehand. Check out the miniature teleporter against the wall with a cactus in it. Not only can you transfer the cactus from one point to the other, but you can remove the cactus and replace it with other objects lying around the room. What a nice touch: the current key story element is also presented in a simple interactive form. You also get to put on your HEV suit before stepping into the teleporter. Putting on the HEV suit is an interesting moment, not only because we see more of Gordon's body than we ever do, albeit only his arms and hands, but because it's accompanied by a musical riff that now plays during the introductory credits of every Valve game. Half-Life 2 is, overall, a musically quiet game. Music is reserved for the most vital moments, rather than being a crutch to communicate tension, as it so often is in games and film. When Half-Life 2's soundtrack kicks in, it's telling you to pay attention.

In any case, the teleportation doesn't go according to plan and your scrambled brains get a peek inside Breen's office. He recognizes you, of course, but I'm more interested in the Combine prisoner pods you see to Breen's left. It's easy to miss them, but they, too, provide a very early glimpse of the future. Again: Valve rarely puts something into its games just to have it there. Remember the glimpse of your first strider back in City 17? That wasn't for show: that was Half-Life 2's version of Chekhov's gun. Those pods mean something, and while you may not consciously notice them, they become part of the game's narrative tapestry. Chekhov would have been proud of Valve's ability to keep narrative elements relevant. Valve also applies Chekhov's principle to gameplay. For instance, in Half-Life 2, you don't get to take control of a mounted gun if there's no reason to use it.

Crowbar and Sickle

Action! Physics! The journey is finally underway, but your crowbar isn't much help against the Combine soldiers firing at you in the distance. Fortunately, it isn't long before you grab a pistol, though even after you've taken down a few Combine, there's always something even more powerful suppressing you, such as the gunship that dogs you as you travel to the canals. As phenomenal as Half-Life 2 is even today, there are elements of it that come across as rather quaint, such as the insanity of the ragdoll deaths and the all-too convenient placement of explosive barrels. (What are those barrels doing there?!) Even with the action underway, Valve continually sends the message that Half-Life 2 is not primarily about shooting. Luckily, it's not just about stacking cement blocks either. (Does anyone like that puzzle?)

A few notes about this level before moving on. First: the introduction of barnacles is handled incredibly well. A barnacle's tentacle pulls up a crow and draws it into its maw. You know in 10 seconds what a barnacle does and what makes it dangerous without the game having to cut away to a tutorial video to show you. Moments later, you discover that a barnacle will latch on to anything, even if it isn't edible. Again, you are being introduced to an important behavior without Half-Life 2 making a parade of it. Second: Valve is very good at designing levels that subtly draw your attention to enemies and point of interest. Barnacles are often placed on ceilings next to lights, for instance, ensuring that you notice them.

Soon after begins the oft-discussed and oft-criticized Water Hazard level. It's important, however, that this sequence exist in the game where it does. While we have had glimpses of the resistance, and how the One Free Man symbolizes their struggle and future emancipation, Gordon is not yet entrenched in this group, and their safe havens are few and far between. "Run, Gordon, Run" would have been an apt title for the next few hours of the game, which reinforce Half-Life 2's lengthy narrative and gameplay arc showing Gordon slowly gaining control.

Throughout this arc, Gordon Freeman is a man who doesn't make things happen so much as he's a man to whom things happen. That may seem like an unlikely attitude in a genre in which shooting people is your primary goal, but it's not so uncommon in fiction, and science fiction and fantasy in particular. This is the nature of the "chosen one" narrative: the chosen one has not decided upon his or her own path. Sometimes it's a deity making the decision (The Stand's Mother Abigail); sometimes it's a prophesied destiny (The Wheel of Time's Rand al'Thor, Harry Potter); and other times it's luck, circumstance, or the sheer force of social upheaval, as is the case with Doctor Freeman. (As G-Man says, he is "the right man in the wrong place.")

Valve, in turn, underscores its Chosen One narrative with several sensible storytelling and presentation decisions. Gordon doesn't speak, we never see his reflection in a mirror, and we don't even see his arms and hands when he pilots the airboat. The Half-Life series occasionally receives flak for the inert nature of its protagonist, but Gordon's silence is a vital artistic choice that emphasizes his lack of agency. Alyx and Barney both have a little fun at Gordon's expense before the teleporter incident, pointing out his muteness (as well as his MIT education), but Valve is wise in this case to acknowledge their storytelling choices and move on, allowing those choices to coalesce into the greater Chosen One tale.

In our eyes, individual terror is inadmissible precisely because it belittles the role of the masses in their own consciousness, reconciles them to their own powerlessness, and turns their eyes and hopes toward a great avenger and liberator who someday will come and accomplish his mission.

Vladimir Lenin, Why Marxists Oppose Individual Terrorism

Unsophisticated minds continue to imbue him with romantic power, giving him such dangerous poetic labels as the One Free Man, the Opener of the Way.

Dr. Wallace Breen, Half-Life 2

An apparent weakness notable in Water Hazard and the few chapters beyond is that the Combine don't represent much danger, which runs counter to the understanding that Gordon is not a soldier. The HEV suit itself provides some counterpoint, offering protection from both physical harm and radiation, but Half-Life 2 is an easy game on default difficulty, and it seems implausible that Gordon would so easily mow down these grunts with a pistol. The upside is that the initial ease allows Valve to stick closely to a predictable but understandable gameplay arc in which the tension, difficulty, and combat enjoyment crescendo over time.

The early rhythm sets up this arc extremely well. You spend the majority of these levels not shooting guns, but speeding through canals, avoiding gunfire, and occasionally disembarking to solve a few physics puzzles and explore a few structures. This may sound boring, but Half-Life 2's pacing is masterful, finding new ways to diversify the adventure, and establishing itself not as a straight-up shooter, but as a first-person adventure.

Some of this diversity arrives by way of subtle but expert storytelling. In one facility, you once again find a monitor broadcasting a message from Dr. Breen, but the message has changed, and he now warns the populace of imbuing Gordon with "romantic power," and suggesting that doing so is "magical thinking." (This speech, of course, calls to mind Breen's earlier speech in which he warned of instinct and "superstition." "Be wise. Be safe. Be aware," Breen suggests, again reminding us that the powerful would have us choose between security and liberty. Remember this broadcast when viewing future ones; Breen has yet to express the panic that creeps into his future speeches.

Other diversity comes within the action sequences themselves, many of which incorporate physics (crouch and push a cart down a walkway to avoid gunfire), put you behind a mounted gun (again, you do not see Gordon's hands actually grasp the hardware), and vehicular chase sequences. (Remember: Half-Life 2 heeds Chekhov's principles; if you can take control of a mounted gun, you must have a reason to use it!) Throughout all of these examples, the attention to pacing detail is superb. Consider the warehouse battle, which emerges as the game's first somewhat challenging sequence. The addition of the Magnum to your arsenal just preceding this fight is a judicious development decision.

Before we take this hovercraft ride to its conclusion and find our way to Eli, I'd like to again call out Half-Life 2's environments. The Eastern European setting has already been more or less established by this point, but your ride through the canals has drawn a more specific parallel: The Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Three years after Half-Life 2's release, the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series would eventually face this disaster head on. The Chernobyl connections here are less overt, though rather obvious upon examination. Consider, for instance, the images below, which compare the tenements of Half-Life 2 to those in Pripyat, Ukraine, the town most affected by nuclear disaster. The game explores other Chernobyl parallels in the trainyard and at Nova Prospekt, and while the primary thematic connections are obvious--radioactive hazards are common in Half-Life and its sequel, hence the HEV suit--there's a less obvious theme running beside them. Namely, the secrecy of the Soviet Union's response to the Chernobyl disaster, which was almost Combine-like in its tight control over information.

Locals learned of the accident not because they were informed, but because they began to suffer from life-ending illnesses in a matter of hours. It wasn't until a Swedish nuclear plant detected the Chernobyl radiation that the Soviet Union issued their first statement, which came two days after the meltdown: "There has been an accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. One of the nuclear reactors was damaged. The effects of the accident are being remedied. Assistance has been provided for any affected people. An investigative commission has been set up." Half-Life 2's appropriation of the Chernobyl incident is chilling not just for recalling the horrors of a nuclear event, but for its subtler references to a regime dedicated to keeping the masses uninformed. Like the Soviet Union, the Combine keeps its citizens ignorant as a means of control. It's difficult to "be wise, be safe, be aware" when your wisdom is limited by your own government--and by a Stalinesque figure who presides over an entire planet's populace.

Your time with the hovercraft comes to an end when you reach your destination, but not without the first sign that Gordon might be able to lead a revolution he never asked to be a part of. I speak of the boss fight versus the mine-dropping gunship. The music kicks in when you leave the hangar after being granted your own vehicular weapon, which sets up the urgent minutes to follow, which include shootouts on land as well as on water. The concluding gunship battle does a fantastic job of bridging the gap between Gordon's early hours as prey and the revolution that will ultimately come. Gordon, the hunted, must avoid the mines and stay on the move lest he fall victim to the oppressors. Gordon, the hunter, must attack in return if the uprising is to succeed. His success, just he is about to meet Eli and Dr. Judith Mossman, is important to both researchers, though for very different reasons.

To come in Part 2: Playing catch, playing with gravity, and going to Ravenholm.